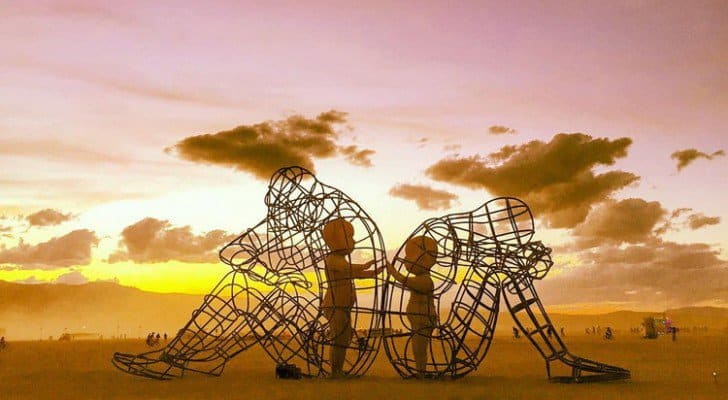

“Love” by Alexandr Milov. Photo © 2015 by Oleg Yarov. Used with permission.

“Love is our true destiny. We do not find the meaning of life by ourselves alone – we find it with another.” ― Thomas Merton, Love and Living

Is it just cliché to say “love is all you need?” Perhaps so, but in today’s complex and demanding world, we can tend to overlook the role that connection and bonding play at the core of our lives.

Why are we driven to such extreme states to gain or regain connection? Simply put, it is deeply wired into our survival instincts. When we understand how and why relationships are so essential to us, we can start to understand how to work with the “mystery” of love.

The Enneagram can help us understand how we miss each other in love, and how we can find each other again. However, each enneatype also adds layers of interpretation on top of the connection dance that plays out, which can make it trickier to see through to the heart of the matter.

According to Dr. Sue Johnson, the main reason people seek counseling, therapy or coaching is relational distress. Our relationships affect how we experience ourselves in the world at all levels. The quality of our connection matters as much as, and sometimes more than, our physical sustenance.

Connection Is Why We’re Here

Human infants have the longest and most dependent youth of all creatures during which we truly are vulnerable and dependent on others for our safety and well-being. Maintaining our connection with caregivers is actually the basis of getting our more “primitive” survival needs met (food, shelter, etc.). So it makes sense that the quality of connection in our primary relationships continues to be the main determiner of our feeling of safety and satisfaction in life.

As mammals, we “regulate” one another through attunement and responsiveness. Mirroring from others is the primary way we assess whether we are “OK” or not. It is most clear when we are young that we depend on this, but it is a life-long condition and intelligence. Consider how often you are “reading” those around you by even the tiniest flashes of expressions across their faces.

When we receive this attunement in a solid and consistent way when we’re young, we tend to develop a healthy independence and interdependence that doesn’t feel overly anxious and needy. But that doesn’t mean our need for connection stops or dims as adults.

Author and professor Brené Brown concludes, in her book Daring Greatly, after years of social science research, that “Connection is why we’re here; it is what gives purpose and meaning to our lives.”

Cultural programming can get in the way of our respecting this, however. Many of us have commentary in our heads that tell us that needing connection is childish or co-dependent. When we are hurting or scared as adults, it can feel risky to reach out for others. Aren’t we supposed to be independent and manage our emotions on our own? What would it mean about me if I really need you to reassure me in this moment? Am I too needy?

And our enneatypes can add particular flavors to these universal ways in which we disconnect from ourselves and those we love.

How We Lose Each Other

All relationships go through frequent cycles of connection and disconnection. It’s actually how it works. What seems to matter most however, is not whether or even how often we fight or get distant, it’s how we reconnect that matters most. Dr. John Gottman, world-renowned relationship researcher and author, posits that a happy couple’s “secret weapon” is their ability to repair effectively.

Being aware of our Enneagram lenses greatly helps us with the ability to assume the good intent of the other and to soften our conviction that we see things fully. Instead of assuming that my Type Seven coworker is a flake who doesn’t care about the team, I might remember that she is a passionate contributor who gets stressed when her sense of freedom and possibility are cramped. I might then think about how to engage her in a new way.

We disconnect from each other for lots of reasons. We may be experiencing stress from work, about finances, from the loss of a loved one, with a serious health issue, or from a difficult situation with a child. These are times when our need for connection is likely to increase. But even without facing extra stressors, we may be uncomfortable reaching out, or we may not know how to seek connection in an effective way.

As if our history and current life experiences weren’t enough to contend with, our enneatypes add familiar storylines to our relationships that can make it hard to see reality clearly in the moment. The more stressed we are, the more our personality lens wants to insist on “helping” us to see things according to the usual program.

For example, at Type One, when my partner seems distant to me, I may subconsciously think, “There’s something wrong with me. I better shape up and do better.” Or I might blame or criticize the other, “Why can’t they appreciate me? They’re self-centered and irresponsible.”

Either of these types of narratives ultimately make it harder for me to come toward the other in a balanced way to express my needs or concerns. They certainly also make it hard for others to feel my heart and needs in order to respond to me in turn.

The themes and storylines common to our type structures determine which cycles of connection and disconnection we are most likely to encounter. Below are some (not exhaustive) examples of the mindsets that start the experience of disconnection.

“Disconnect” as I’m using it below doesn’t necessarily look a certain way- it could be withdrawal, volatility, disassociation, etc.

Type 1 To connect, I try hard to be a “good” partner, parent, etc.

I disconnect when I feel resentful, or don’t express my needs.

I tell myself the story that I am or that the other is bad/wrong.

Type 2 To connect, I try to find the other’s needs and meet them.

I disconnect when I feel unappreciated, or thought ill of.

I tell myself the story that love equals positive regard.

Type 3 To connect, I act in ways I think will be approved of.

I disconnect when I sense another sees me negatively.

I tell myself the story that I have to earn love.

Type 4 To connect, I offer my deep feelings to be understood.

I disconnect when I feel misunderstood or afraid I’ll be left.

I tell myself the story that I am or the other is not enough.

Type 5 To connect, I share musings from my inner world.

I disconnect when I feel demanded of or intruded upon.

I tell myself the story that I can’t handle the perceived demands.

Type 6 To connect, I try to be steadfast and protective.

I disconnect when I don’t trust.

I tell myself the story that the other has the power to ruin things.

Type 7 To connect, I share good vibes and ideas.

I disconnect when I feel limited or stifled.

I tell myself the story that I need to get away from pain.

Type 8 To connect, I engage directly with gusto.

I disconnect when I feel weakness in you or me.

I tell myself the story that I need to stay in control.

Type 9 To connect, I go with the flow of the other.

I disconnect when I feel pushed or ignored.

I tell myself the story that I don’t matter.

These type-specific themes are just the story line that plays out. The plot is often at a deeper level underneath the things we are frustrated about with each other. And the plot is not nearly as diverse or complicated as the story lines.

I Just Want to Be Loved! Is that So Wrong?

Basically, we all want to be wanted, appreciated, and specially cared for in our primary relationships. All nine types do. All genders do. All ages do. All cultures do. As Dr. Sue Johnson emphasizes, we are all scanning to confirm or deny this fundamental question: “Are you there for me when I need you?”

The human reflex of projecting meaning or “story” onto almost anything in relationship makes it very easy for us to believe our people are actually not there for us. This creates primal stress. Some examples:

- My father’s coping style has me feeling chronically rejected.

- My typical way of expressing myself makes my boss feel intruded upon.

- My partner’s criticism makes me feel so incompetent, I lose all my skills.

- I tell myself that if I were to reach out to my friend that they would find me pathetic.

- I regularly miss my child’s style of reaching out for connection, and see it as annoying.

In elemental terms, when we are the one in relational distress, we see the other as a threat to our well-being or survival. From this position, it makes sense that we wouldn’t feel generous or empathetic toward them. Thus, the dance of disconnection begins. We each feel the other is not there for us in the way we need, and we want the other to shift first before we have empathy.

Stay tuned for an upcoming post about what we can do about these predictable disconnections. You will learn how you can work with yourself to turn toward your needs, and to reach out to the other, in ways that will bring connection back swiftly and strongly.

Questions you might ask yourself:

- What did I learn when I was young about how to cope with disconnection? Can I see that belief or strategy at work in my current life? How is that affecting my experience today?

- When I feel disconnected from another, can I wonder how my type bias might be scripting the situation? What other ways of seeing the situation might be possible?

- In which ways do I tell myself people are not there for me? Can I look for evidence to the contrary?

Please share your reflections below.

4 Responses

Very Interesting article Sarah. Several of your examples hit home for me.

I’m glad it resonated for you. It’s some pretty profound wiring we have, isn’t it?

If a picture is worth a thousand words, the picture above says it all. Having the imagery helps visualize and experience what is going on. Thank you.

I agree. When I first saw this photo at a workshop by Susan Johnson PhD, I felt it penetrated into what I’m almost always working with in some form with clients, as well as in my own relationships.